From Adversity to Advantage: Building Careers After a Setback

By Claire Harbour and Antoine Tirard

When we set out on our journey of exploring big career transitions seven or so years ago, we probably did not plan to find ourselves writing about criminals, whether actual or presumed. We started with this question: what happens to those who experience a major setback or an “adverse incident” in their life or career? Our hypothesis was that it would almost always lead to a redemption of some kind, but that this redemption or renaissance is far from easy. For a person who has been incarcerated, or someone who has suffered a very public humiliation, most of the usual tools are taken away, when it comes to networking and applying for a new job, and so greater creativity, resilience and more must be required, we thought.

In this article, we delve into the stories of two individuals who have suffered massive setbacks in life and career. Both faced the tremendous uphill struggle post-incarceration or misfortune of “how do I rebuild my career?”, whether purely in terms of making a decent living financially, or with regard to doing dignified work once again. Our premise is that while these examples are extreme, to some extent, they are excellent indicators of the absolute essence of what is required to succeed in one’s career, and that the re-builders have a great deal to teach the “ordinary builders” of career that most of us are.

From Rock Bottom to World Changer: The Inspiring Story of Shelley’s Redemption

Shelley’s father first got her drunk when she was eleven years old, and his only rule as he tried to be her “buddy”, growing up, was that when she “did hard drugs, to do them at home”. Her mother’s “addiction of choice” was a series of boyfriends, and so Shelley and her brother grew up with no positive role models, and came a very clear second choice in their parents’ priorities. She started using methamphetamine at 16, and cocaine shortly after that. In the “one year I got sober” she went to community college and made it to the Dean’s list, but “the problem is I didn’t stay sober very long. I hurt my wrist, I was prescribed Vicodin, and the downward spiral set off once more”.

For more than a decade, the young woman drifted from one high to another, resorting to begging from friends and petty theft to fund her habit. During a rare period where again, she had managed to get sober, she was tipped off by a friend that the oil boom in North Dakota could be valuable for her: “bartenders were making a thousand bucks a night”! A couple of ads and phone calls later, she had a job, and put all her belongings in her car. Her roommate waited no longer than the first night to offer her some meth, and she slipped right back in to using. However, Shelley rapidly spotted a business opportunity. It was tough to find “quality drugs” in that remote area, and she knew that she would not be alone in preferring a better class of product. So, she bought “an ounce” from a friend across the border in Sacramento, for nine hundred dollars, and sold the twenty-eight grams for two hundred and fifty dollars each. And she did it, again and again and again.

She loved her fancy life, even though she was destroying her health as well as playing with fire. She believed she could “outsmart the local cops, who were hicks” and indeed she did for quite some time. Eventually the FBI began surveillance on her, but even this she saw as a joke, waving goodbye to them as she drove off. Not long after, she was arrested with the full show of blue lights, guns and loudspeakers.

The utter horror of the local jail soon had her asking herself some big existential questions, but by the time she was in a halfway house she was already using drugs again, and discovered she was pregnant. This rock bottom was undoubtedly a blessing in disguise, as it was the moment at which she remembered her faith, and signed up for a recovery program “literally just down the road”. In the end, she was sentenced to four years in prison. Of course by then she had given birth, and her son was with her mother.

There had been one major slip in Shelley’s behavior while still in the halfway house that led to her almost losing everything, but this provoked a literal “come to Jesus moment”. She prayed to have her heart “changed” as she knew she had hardened too far. Shelley began “noticing all the positive things around me”. She followed the path of positivity doggedly, and when she arrived in prison, she began signing up for all kinds of classes and programs, ranging from anger management to trauma. She still has the certificates for each and every one of the almost one hundred courses she took. The people Shelley spent time with were deliberately chosen by her because they were wanting to make good of their lives, and she gradually “reprogrammed” her mind and her heart.

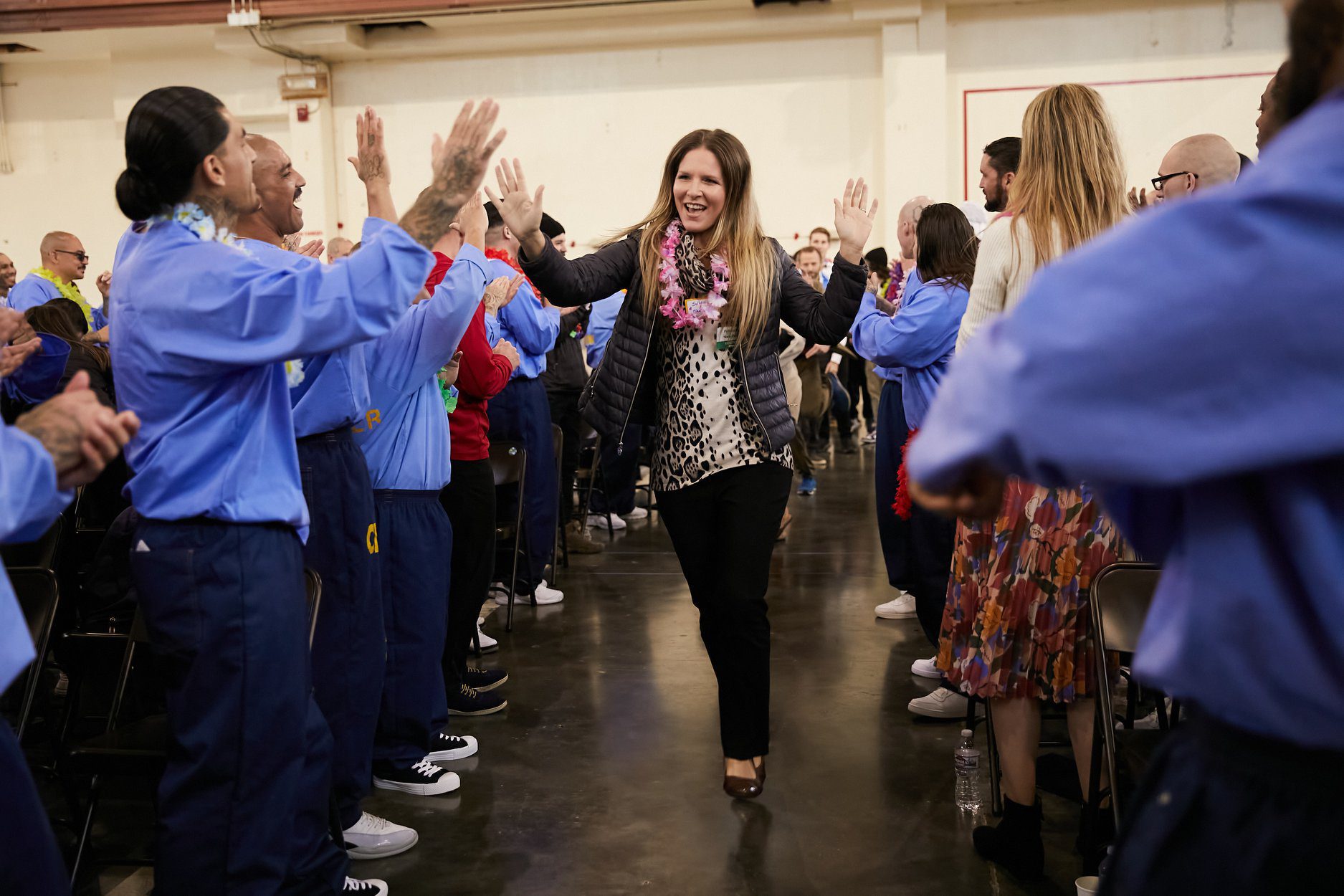

As she prepared for a return to life without bars, Shelley realized that it was going to be challenging to get the kind of work she now wanted to have. Her vision was clear: a role at a tech company, and six figures “without a college degree and with a record”. She journaled, she prayed, she manifested however she could, and on release from prison, she entered a halfway house in a rough area of San Francisco with new resolve. With funding from the state she was able to become a “straight A student” in computer science, and then serendipity showed up. She overheard a TV report about a Job Readiness program for the formerly incarcerated; and what is more, it was literally just across the street from her house. Not only did she learn important skills, but also there was support with networking with all of the major Silicon Valley tech companies. She connected particularly well with two women at Microsoft, who said they would emphatically support her in any applications she made. The Microsoft retail store looked like a great springboard from which to start, and a job came up. The store manager was enthusiastic, having heard from Shelley’s two advocates. She made the offer on the spot.

In the flurry of emails that ensued, one came in with a link to information about anti-discrimination laws local to San Francisco, giving a “Fair Chance” to former prisoners. This boosted her confidence no end. Unfortunately, a call came in saying “we’re not moving ahead with your hire”, and Shelley was devastated. Also outraged: “it’s like wearing a pair of invisible handcuffs; the slate is not wiped clean at all”. While expressing her frustration to her mother, she was reminded of the fair chance email, and decided to give them a call. The person she spoke with agreed to take on her case and to “fight the giant”. The battle was won, but by then the vacancy was filled.

Shelley believed she would never make it. After several days of dejection, she was surprised to receive a call extending an offer for a job. The whole neighborhood probably heard her shout for joy… When her uniform Microsoft shirts arrived in the mail, that was when it sunk in: “I work for Microsoft”! On starting, Shelley was made to feel the store manager’s doubts, but she assured her she would “ work really hard and go above and beyond”. Within two months she had been elected “Most Valuable Professional” award-winner by all her peers; a status that usually takes a year to reach. Promoted to a technical role within a few months, Shelley was on fire. Her spare time was taken up volunteering and speaking about fair chance hiring, and it was this which led to an email invitation to apply for a job in the corporate part of the company. A senior executive had seen a TED talk she had done to encourage hiring the formerly incarcerated and offered to “do all he could to help her”.

Fierce competition prevented her from obtaining the first corporate role, but she was asked to wait a few months for a role they were going to create for her, as a Surface Technical Solutions Professional . Once that came up, a background check had to be done once again, for the shift from retail to corporate, and she was “flagged”, only to be saved by her high-level ally, who stuck his neck out, expressing his conviction she would be an invaluable addition to the team. Eventually they acquiesced, and she began a job in the swanky downtown office building shortly thereafter.

It was a massive change, and difficult for Shelley, but she was “enjoying drinking from the firehose”. A restructuring was done, and she was asked to take on a sales role, despite having little background in that area. With a new manager’s encouragement, she excelled, and she finished her second year as the top Surface seller across the globe.

Currently, Shelley continues to achieve multiples of her targets, wins awards and makes a very healthy six figure salary. She beams as she tells us this part. What is more, her advocacy work is making an impact internally: the company has joined the Second Chance Business Coalition, a group of large private-sector firms committed to expanding second chance hiring and advancement practices, and she regularly speaks at events. “Storytelling is a powerful tool that will change the world”. Her next goal is to bring CEO Satya Nadella with her to volunteer in prisons, and we bet she will make that happen.

From Arrest to Appreciation: Frédéric’s Journey of Emotional Resilience

Frédéric was in a high-profile arrest at JFK, just under 10 years ago, where he was accused of bribery of foreign public officials and conspiracy to bribe. His then employer, Alstom, did little to support his defense and it became increasingly apparent to him that he was taking the hit, to save higher-placed executives’ hides. He was kept in custody and denied bail, for 14 months, suffering the ignominy of being fired from his company six months after his arrest. A series of roller coaster events ensued: he finally secured bail for a couple of years, thanks to friends, and was then condemned to a two and a half year prison sentence. Endless pages have been written on the vicissitudes of the case itself, and there is indeed a book where you can explore that, but what interested us was the emotional ride Frédéric had, and how he managed his career after this incredibly difficult period.

Born in a small town in the north of France, Frédéric had always aspired to life overseas. His parents encouraged the hard work required to enter a top engineering school, and then to start first as a state apprentice, then as a graduate trainee, a long career at Alstom. This journey began in Algeria, and quickly on to the United Kingdom. His broad range of skills was quickly spotted and his rise meteoric; businesses were grown in India and the Philippines, and Frédéric loved working with innovative people, and to contribute to a rethink about energy generation, private power plants and so on.

Doing significant business in Indonesia often requires some form of bribery – the country is poorly ranked in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. When Frédéric was working there, he was not blind to this context. There was a convoluted process set up in the company to ensure compliance, and he recalls that “everybody played a role; however this did not figure in my day to day work. I was never choosing an “agent” directly. I felt that this was properly taken care of by the company and the process.”

The isolation of not only being in a high security prison dorm far from friends and family, but also feeling the anger around having been abandoned by his company would have pushed many over the edge from the outset. But Frédéric used steely nerves to shield his wife and family from his own stress, and to channel his energies in the most useful ways. He began to journal, from day one, and created a daily schedule for himself, as if he was going “to the office every day”. He divided his days into the various tasks that were important, mostly about trying to understand the complex laws around corruption at least better than his lawyer did. This was done without any access to internet, and so all the more admirable. He also began journaling from the outset, although he did not necessarily expect this to turn into anything other than a daily catharsis. Socially, the system was complex, but he soon found himself hanging out happily with one of the top guns of the “French Connection” drug-smuggling organization. Other European inmates emerged, including a number of Greeks. These white collar felons found enough similarities to make friends easily, but suspicion reigned overall, making things grim and tough to navigate for Frédéric.

He was consciously thinking “all the time” about his career, for two main reasons. First and foremost, he was very clear that nobody was going to employ him. Not only was there not a big supply of executive jobs for ex-convicts, but also, the years spent waiting for his sentencing made it impossible to have a “clear runway”, due to the uncertainty of when and how the sentence would come. Next, he was becoming an absolute expert in the laws of compliance and corruption, having studied “all the cases available” and then some. So, discreetly, even while still in the midst of waiting for sentencing, Frédéric began to consult, lobby and pressurize all the parties it was relevant to touch. He “wanted to send a message to the French government, to serve, to be useful, valuable…”. “I was patriotic, and I was disgusted by the subsequent sale of Alstom Energy to the US. I wanted everybody to understand the geopolitical horror of losing sovereignty.”

The lobbying needed funding, and what Frédéric realized was that he could achieve what was needed by working with companies who needed help with their own compliance issues, teaching in schools where lessons were needed in the strategy of this new way of doing and protecting business, and so on. This experimentation and subsequent corporate world re-entry was made possible by Frédéric’s unique position and ability to bridge the corporate world with the legal world. He had developed an expertise and a human business language to get around the legal jargon most find complicated, and he was welcomed into the corporate world without any hint of his reputation being damaged.

Writing his book, The American Trap, as it emerged from his journaling, certainly allowed Frederic to work through and then pass on his own understanding of the high stakes game he was caught up in, and also allowed him to be seen as a valiant, positive character. Press was extremely positive, and he even won a human rights prize. He was touched by how much people were inspired to reach out to express sympathy, and indeed to undertake studies to avoid such events in future. Having suffered the loss of all but a handful of his close friends, though recognizing that he would very possibly have played similarly “bad cards” if the shoe had been on the other foot, he emerged realistic and free of ties. His understanding is striking. “Whatever you think about morality and ethics, until you are in this kind of situation, you don’t know what you might actually do”.

Trust remains a significant factor for Frédéric. He felt horribly betrayed at so many levels, through no fault of his own. He is happy that the consulting work that he continues to do now allows him to choose the people he works with, but he admits to still finding it hard to rebuild his capacity to trust. Being thankful for small mercies helps him, focusing on parents and grandparents fighting in world wars, those who were suffering terrible sickness, and more, assisted him in coping. And today, now the actual nightmare of prison is over, the new Frédéric is a changed man. No longer always in a rush, focused only on jobs and deals. Now he appreciates every single moment. “To have a coffee while sitting on a café terrace is a huge privilege, and I appreciate everything much, much more”.

Surviving Career Setbacks : a Conversation with Frédéric Godart (INSEAD)

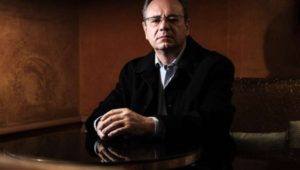

Frédéric Godart, Associate Professor of Organisational Behaviour at INSEAD, wrote a case study about Al Gore, one of the most influential vice-presidents in US history who, in 2000, failed to secure what is probably the most powerful job on earth – the presidency. The case describes how Al Gore nonetheless reinvented himself after the defeat and built a successful and impactful post-political career in environmentalism. It shows how one can reinvent oneself after a major career setback by using knowledge about human dynamics and organizations. We reflected with Frédéric on our subjects’ journeys to redemption. Here is what emerged from our conversation

Where do you see the similarities and the differences between Shelley and Frederic (Pierucci), and Al Gore?

To look at what is going on with these three individuals who managed to survive major setbacks and reinvent their careers, I like to use the organizational DNA (“OrgDNA”) model, which consists of three main elements: Architecture (or Structure), Culture, and Power and Influence (including networks).

Frederic was masterful in getting an understanding of the formal social structures, so as to play on them. While in prison, he studied the legal systems of both France and the US, and used the dynamics of each to his advantage. He also had disciplined routines in place, which underpinned his efforts. As he developed his understanding the of the structures, he was also playing with his ability to deal with two national and legal cultures, as well as understanding the rules and norms of each, to stay connected to those who could support him. And finally, he had a powerful network and influence, with many friends and family even helping him financially to make bail. He made the best use possible of his sphere of influence, despite the stigma attached to his judicial status.

On the other hand, Shelley was dealing with the deep stigma of not only having the system trying to take her down, but also having actually committed the crime of which she was accused. Thus she was almost totally lacking in power and influence. She recovered by turning her stigma, her weaknesses into strengths: humility, hard work, sheer intelligence and grit – a total refusal to stand down. She, too, used discipline and focus as a structural underpinning in her endeavors. Shelley created an alternative network, in the local coding rehabilitation organization, and made massive efforts in terms of connecting with, engaging and convincing those she was able to meet and influence. And finally she used culture by moving towards the tech sector, which values mavericks and outliers, thus elevating her chances of acceptance.

Al Gore was in a public position and of course he was playing at a different level to our other subjects. His major advantage initially was his expertise and influence, derived from his time as one of the all-time most powerful VPs as well as his privileged family background and education. He built on that knowledge and connections to create his focus on sustainability. He put the interests of the nation and the planet above his own, and this supported his reputation as he rebuilt.

Does this mean that there are fundamental differences in how to recover depending on the type of setback experienced?

There is indeed a key difference. Recovering from stigma – the case of Frédéric and Shelley – is different from recovering from defeat – which Al Gore experienced. He was dealing only with a setback: it was a “game” so to speak (an institutionalized and codified process) and he lost. For Frédéric and Shelley, they first had to embrace and own their situations. They also found a way to fight back and reframe themselves and their circumstances. Al reframed his defeat, but he did not have to reframe himself in the same way. We see however what is common to our three subjects: making sense of all that has happened was key to each of them in supporting their recovery. In that sense, using structure, culture, and power and influence comes from a redefinition of identity which then provides the motivation and energy.

What advice do you have for any professional who is trying to recover from a setback?

Those who succeed at this appear to demonstrate these five abilities.

1 – Structure – You need to be well aware of the formal aspect of things: the rules, the institutions, the routines you can set up to fight back.

2 – Culture – You need to “read the room”. Understand what the rules and values of the place or context you want to get to are. If you want to reinvent yourself, you need for others – the relevant audiences – to accept you and thus, learning to play according to their rules and values is crucial.

3 – Influence and meaningful relations – Politics is not about manipulating or pushing lies, rather about convincing people and creating coalitions that can support you. It is about being protected. It is also about improving your projects and understanding of situation by confronting your ideas with your friends and allies.

4 – Resilience from identity – Don’t give up. Look for the character and inner motivation and grit that are somewhere inside you, and come from your (possibly evolving) identity. Seek out the right connections to people who are going to challenge you as well as encourage you: mentors, trustful relationships that will encourage the willingness to change.

5 – Higher Order and Guiding Principles – All those who succeed at this kind of redemption seem to have a strong sense of mission: Shelly had her faith, Frederic his sense of justice and Al his mission of saving the planet. This mission, and the values driving you, underpin your own authentic leadership.

Rising from the Ashes: How Emotional Management and Resilience Lead to Reinvention

While Frédéric Godart’s thoughts have given huge sociological insight about redemption, there is also the question of how do we each better arm ourselves to reinvent after a setback? Inevitably that is going to crop up in a long life. So here are some ideas derived from our stories, that we believe might help.

1 – The importance and need to manage anger while in prison or during the state of adversity, and turn it into a positive energy to help rebuild a future life

2 – The fact that old horses can learn new tricks. Whatever the crime or incident, our subjects found new ways to behave, despite the struggle that required.

3 – A huge key to these “new tricks” is the creation of a disciplined, mindful lifestyle, of study, chronicling and reinvention, from the outset

4 – Brand new personas can be created, whatever the past. This is neither easy nor watertight, but new approaches and behaviors, new social connections and circles, renewed faith or courage, and different convictions and beliefs can shape who we are to a huge extent.

5 – It is not only possible but desirable to build a narrative about what has been experienced and turn the negatives into something useful for others.

6 – While “classic” networking with former contacts may have become impossible, being creative with new sources of ideas and energy can be critical

7 – Finding faith, hope and optimism, whether via religion, justice or otherwise, is an incredibly powerful engine to reinvention

So what can “we, the more ordinary people” learn from all of this? While we the authors certainly hope that most of us will not go through such drastic experiences, we all experience the need to transform and reinvent ourselves in our lives and careers. The examples set by Shelley and Frédéric can definitely be of inspiration as we navigate those changes, and serve as an incredible reminder of how delicate our position in life is, and how we need to be as mindful as possible of how we treat it.

Sign up

Sign up to receive regular insightful news and advice on managing your career and receive a free gift. Inspiration delivered straight to your Inbox!